Issue #64

Hi all —

The cottage I recently moved into is filled with little knick-knacks my maternal grandmother gave each of her grandchildren over the years. The little Ganesha statues on shelves. The dancers carved in bronze metal propped over the heater. The colorful mirror in the bathroom. The children’s books by Enid Blyton and other British writers she loved in dusty cardboard boxes I hope to pass on to my future kids someday.

But something most treasured is now missing from the top shelf of my refrigerator here — far more valuable than limited supply Trader Joe’s pumpkin butter or California craft brew: a nondescript glass bottle of sambar podi (powder), made by my grandmother Ambulu Paati.

Like my parents, brother, uncles, aunts and cousins, we had never bought sambar powder. I never made it myself, either. It was always a steady supply from Paati, usually transported in triple-packed Ziploc bags from Chennai — my grandma breezing the goods through TSA and customs security checks like the seasoned traveler she was — “Hehehe. It’s a homemade spice, officer. Want to try some?” I imagine her saying.

It feels like it’s been three years, but some days, thirteen. Distant memories are getting hazier. I worry they’ll get even hazier as my hairline recedes. So I try to remember. Ambulu Paati passed away just days into 2021, the cancer had worn her physical body of only 76 years. As I wrote at the time, the way she loved was through food. Her love language. There was never just one curry on Paati’s table. Always a feast. A buffet of colorful curries and South Indian staples.

Sambar was a regular on Paati’s menu. Never store-bought or watered down like the restaurants. It was rich, generously full of vegetables and dal, a hearty dish to accompany everything from rice to dosa to idli — or even thayir sadam (yogurt rice). In the U.S., Paati was bold with adapting her sambar, adding local vegetables like Brussels sprouts, red radishes, cherry tomatoes and snap peas to the lentil stew.

I had one bottle of powder left in Colorado. It felt sacred. The orange-ish dust that smelled like a beautiful symphony of masalas and dals. I barely touched that sambar podi for months — except for Thanksgiving the year Paati died, when my cousins and I garnished a potato dish with its aromatic spices, a homage to the first Thanksgiving without either her physical presence or her phone call. That unique combination of spices felt valuable. A calculation only Paati knew. Finishing it would have been a reminder that she is no longer here.

During a move last year, I handed over the remaining gold to my parents. I knew what that meant, but I tried not to overthink it.

My new kitchen has a cabinet I furnished with a library of spices from a hipster, Instagrammable Indian American brand that Paati would probably say is overpriced. I ordered dozens and dozens of spices in colorful tins, but I couldn’t bring myself to buy their sambar powder.

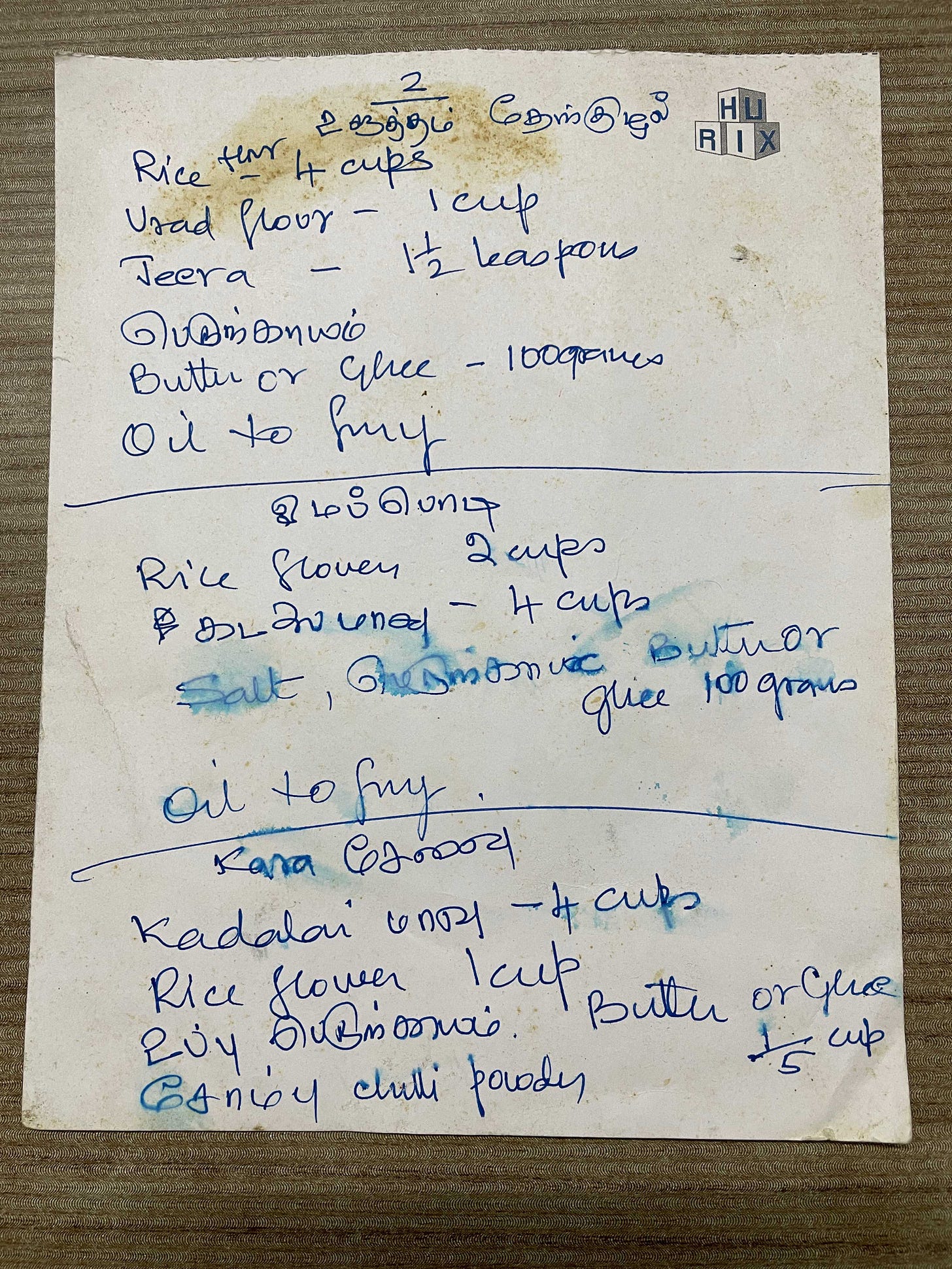

Now, in our family, we are all learning to make it on our own — sans any precise recipe, like most South Asian things.

So it makes me think about the things lost from each generation in diasporic communities. As we move around the world, as loved ones pass away, are these traditions lost? Or adapted? Something made anew?

My mom tries to remember the process the last time she saw Paati make it. It was 2019 in Paati’s always bustling city apartment. Wafts of coriander seeds and dry red chiles spread throughout the air, making everyone cough. Paati was prepping a giant batch of her signature ingredients, packing them into a stainless-steel drum to send off to a mill for grinding into a deep orange-red powder. It would arrive back to be packaged and carried throughout the globe to family across the United States, Singapore and Malaysia.

There’s still a bit of treasure left in my parents’ freezer all these years later. We wonder how it might taste different if we make sambar powder with Rocky Mountain-grown chiles instead of the Tamil Nadu-grown ones Paati would buy from her vegetable lady. Will we be able to tell any difference?

Maybe Paati’s love will be the key ingredient most missing from the powder, my mom wonders. Emotions fuel cooking, she says. The love and devotion Paati put into spending hours preparing the ingredients for us all to ultimately enjoy on our dinner tables.

So will it taste the same? Maybe. Maybe not.

As I settle into the rhythm of the cottage’s kitchen, I’ll inevitably make sambar at some point, I tell myself. I debate between succumbing to a major Indian food conglomerate’s version. So far, I’ve resisted. Or I could just learn to make the podi, as Paati once did, prolonging the tradition of this homemade jewel we all adore.

Thanks for joining the conversation,

Vignesh Ramachandran

Co-founder of Red, White and Brown Media

(Follow Vignesh on X (formerly known as Twitter), Instagram and Threads via @VigneshR.)

Your Thoughts

Please email us to share your feedback, conversation ideas or anything else you’re thinking about these days:

Red, White and Brown Media facilitates substantive conversations through the lens of South Asian American race and identity — via journalism, social media and events. Please tell your friends and family to subscribe to this newsletter.